China’s Soft Underbelly Part 3.5

Policy brief on Self Employment in China: Culture, policy, clannishess, social trust, and institutions

The disparity is also apparent in the North’s reliance on government funding. As China’s economy slows and its old industries dwindle, northern governments last year generated enough revenue to cover less than half their spending. The South, in contrast, was able to fund 55 per cent of its own outlay, according to a recent study from the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences, a think tank affiliated with the Ministry of Finance.

Furthermore, the infrastructure of the South, including the ports, make it a natural destination for foreign capital. This has helped it grow exponentially, as the resource rich North struggled with commodity price fluctuations.

The foreign investment helped the South become an export hub and home to hi-tech industries. Its private sector boomed, with firms able to react more quickly to market forces than the state-owned enterprises in the North.

Liu Qingfeng is a businessman from Liaoning, a northeastern Chinese province bordering North Korea and the Yellow Sea. Liu spent a decade in Shanghai and four years in Shenzhen, before moving to Beijing three years ago. He said that while businesspeople he dealt with from both China’s North and South are pragmatic and fast learners, those in the South are more “collegiate”. This attitude lends itself better to growing a private business, he thought.

“This means small and medium-sized family businesses in the south can expand to a bigger scale. The North cannot compete with that. If you read the story of successful entrepreneurs in the North, many of them are lonely heroes, fighting on their own,” Liu said.

China's North-South economic divide is growing, away from the glare of the US trade war

Historical Background

North–South institutions, social trust, and China’s “natural” business environment

Across imperial and reform-era China, lineage (clan) institutions have been denser in the south and thinner in the north and west. Hand-collected genealogy counts scaled by population show a south-heavy concentration of clans, with weaker presence in northern and western minority regions. This pattern matches classic anthropological mapping of strong southern lineages versus weaker northern ones. Southern areas (Fujian, Guangdong; often extended to Guangxi, Zhejiang, Jiangxi) revived lineages and territorial cults earliest and most intensively after 1978, what ethnographers call the “southern model.” Meanwhile, the “north model” is marked by the absence of land-holding cooperative lineages. That said, we must stress that places obviously mix elements of both models. The divide is a durable tendency, not a hard boundary.

Two deep historical currents help explain why southern clan institutions became so salient:

Neo-Confucian lineage doctrine (Southern Song): A study used exposure to academies with links to Zhu Xi and Lu Jiuyuan (in terms of how far away) as an instrument for today’s clan strength. Prefectures closer to those academies exhibit persistently stronger clan influences.

The 1127–1130 southward migration: When the Northern Song collapsed, officials, nobles, and large northern clans moved south, later forming influential lineages. This shock is a powerful, exogenous predictor of modern clan density and helps identify the effect of clans on regional specialization.

Clan institutions, social trust, enforcement, and capital inside the family

Lineage organizations historically pooled common property, codified rules in genealogies, and enforced behavior through internal governance and ritual life, strengthening intra-clan cohesion. In modern firms this shows up as:

Short-radius trust (high trust in family, low in outsiders),

Resource pooling (family capital substitutes for imperfect local finance), and

Amenity/identity benefits from family control (obligation to employ kin, utility from keeping control).

These channels are observable in micro-data and are stronger where formal contracting and finance are weak. In aggregate, a one-standard-deviation rise in local clan intensity raises family ownership by ~3.65 percentage points, an economically large effect.

For the business environment, this means the south’s denser lineages supply informal enforcement and family capital that substitute for thin formal institutions, while northern locales, with sparser clans, have historically leaned more on state or formal legal arrangements—a difference consistent with long-standing contrasts between informal and rule-of-law regimes in China vs. Europe.

Who thrives where?

Where clans are dense, all firms that rely heavily on relationship-specific investment and contract enforcement gain. At the prefecture level, stronger local clans predict greater specialization in contract-intensive industries, with the 1127–1130 migration used as an instrument to confirm causality. At the firm level, profits are especially higher in contract-intensive sectors when either the regional clan density or the entrepreneur’s surname-specific lineage interacts with contract intensity—evidence that informal enforcement lowers transaction costs.

Thus the southern business ecology of dense kin networks plus thick inter-firm ties naturally favors relationship- and customization-heavy manufacturing and trade, while thinner lineage infrastructure in much of the north nudges activity toward state-brokered or more standardized, formal-contract environments.

Corporate behavior: prudence, reputation, and marketization as a substitute

Lineage norms also discipline behavior. Using listed firms (2001–2016), stronger local clan culture is associated with lower corporate risk-taking, especially when the CEO/president is local or bears a top local surname, consistent with reputation incentives inside the clan. The effect is strongest for private firms, weaker for local SOEs, and absent for central SOEs. Again, these facts highlight the substitutability between informal and formal/state governance. Moreover, marketization and stronger formal governance mitigate clan effects on risk-taking, underscoring a north-tilted path where formal institutions can stand in for kin enforcement.

Intact vs. fragmented clans: what “natural” economies look like on the ground

Ethnographic contrasts show how lineage structure shapes everyday economies:

Intact, cohesive lineage (South Fujian: “Zhu Stronghold”). A stable ritual alliance and dense kinship produced an entrepreneurial road economy (tire repair, fuel stations, logistics), expanding toward distant markets—a self-generated local business base rooted in kin coordination.

Fragmented lineage tied to the state (North Fujian: “Du Village”). Work, income, and even revival of communal life hinged on state-owned/industrial-park jobs, land expropriation rents, and government-organized recruitment. This case thus presents a government-led employment base rather than kin-financed entrepreneurship.

Fragmented/migrant hometown (South Fujian: “West Mountain”). With lineages “of little utility in the economic sphere,” livelihood centered on migrant factory jobs and friend/hometown ties more than clan.

Taken together, we find that intact clans generate place-based, kin-coordinated enterprise, while fragmented clans rely more on state payrolls or external employers. Thus while the fault line of clan density often maps onto south (denser clans) against north (sparser clans), we note that important within-south variation exists.

Shocks and adaptation: pollution, conflict, and flexible stability

Lineage orders are not static. In Jiangsu’s Shijiu Lake region, an exogenous water-pollution shock from 1993 triggered violent conflicts among villages and factories, then morphed into institutionalized, cross-clan responses (elections, associations) as clan elites moderated tactics. The author calls this pattern “flexible stability.” Pollution also split clans internally (well contamination pitting sub-lineages against each other), showing how environmental stress can reconfigure trust and coalition lines well beyond ritual ties.

Thus where clans are strong (often south), shocks are first processed through kin-based mobilization, then hybridized with formal channels; where clans are weak (often north), state and legal mechanisms dominate from the outset.

This history explains why southern China’s “natural” business environment is heavy on bonding trust, family capital, and informal enforcement, favoring family ownership and contract-intensive specializations. In Northern China, meanwhile, firms respond more to marketization and legal upgrading than to kin pressures.

These historical facts thus align with our empirical setup. We have aslow-moving cultural backdrop, whether proxied by rice or genealogies, that conditions how provinces translate marketization, foreign presence, and urban change into entrepreneurship. These knock-on effects express themselves more in levels and cross-sectional responses than in year-to-year fluctuations.

Empirical Results on Self Employment

Specification and estimation

We track five moving parts for each Chinese province, 1992–2024:

Urbanization

Foreign-registered firms

Self-employment (per 10k people)

GEI (gender equality in entrepreneurship)

Marketization

Plus two outside nudges that might matter right now: global volatility (VIX) and each province’s rice intensity (our slow-moving culture proxy).

Choosing the “memory” of the system (how many lags?)

We re-ran the model with 1–10 lags and scored out-of-sample performance (train: ≤2016; test: >2016):

RMSE: peaks around 8 (with a heavier forest, 8 just beats 7).

Wasserstein distance (full distribution fit): likes 7.

Mean |log error|: also likes 7.

Because our policy focus is self-employment, and since that specific equation’s cross-validation prefers 8 lags, we set p = 8 for the baseline and treat p = 7 as a near-tie.

A practical note: long memory “burns” early years. With strict complete cases, p=8 leaves only ~6 usable years/province (186 rows total). Using KNN imputation, we keep ~25 years/province (775 rows). Thus, long dynamics are feasible with imputation. Without it we’d have cut back to p≈5–6.

What actually drives self-employment?

We make the black box legible with grouped permutation importance (how much test error rises when we scramble a whole group of predictors).

For the self-employment equation

Share of total ΔRMSE on the validation fold:

Own lags (self-employment): 73.7%

Marketization lags: 11.9%

Foreign-registered lags: 9.8%

Urbanization lags: 3.3%

GEI lags: 0.6%

Rice (contemporaneous): 0.5%

VIX (contemporaneous): 0.10%

Thus self-employment is hugely state-dependent (history matters), with meaningful spillovers from market conditions and foreign presence. Rice and VIX add very little short-run predictive power once those dynamics are in.

System-wide (average across all five equations)

Foreign-registered lags: 76.6%

Marketization lags: 13.1%

Self-employment lags: 5.1%

Urbanization lags: 3.9%

Rice (contemporaneous): 1.54%

VIX (contemporaneous): 0.03%

Calendar time and simple trends don’t move the needle once the rich dynamics are in place.

Rice as background culture, not a shock

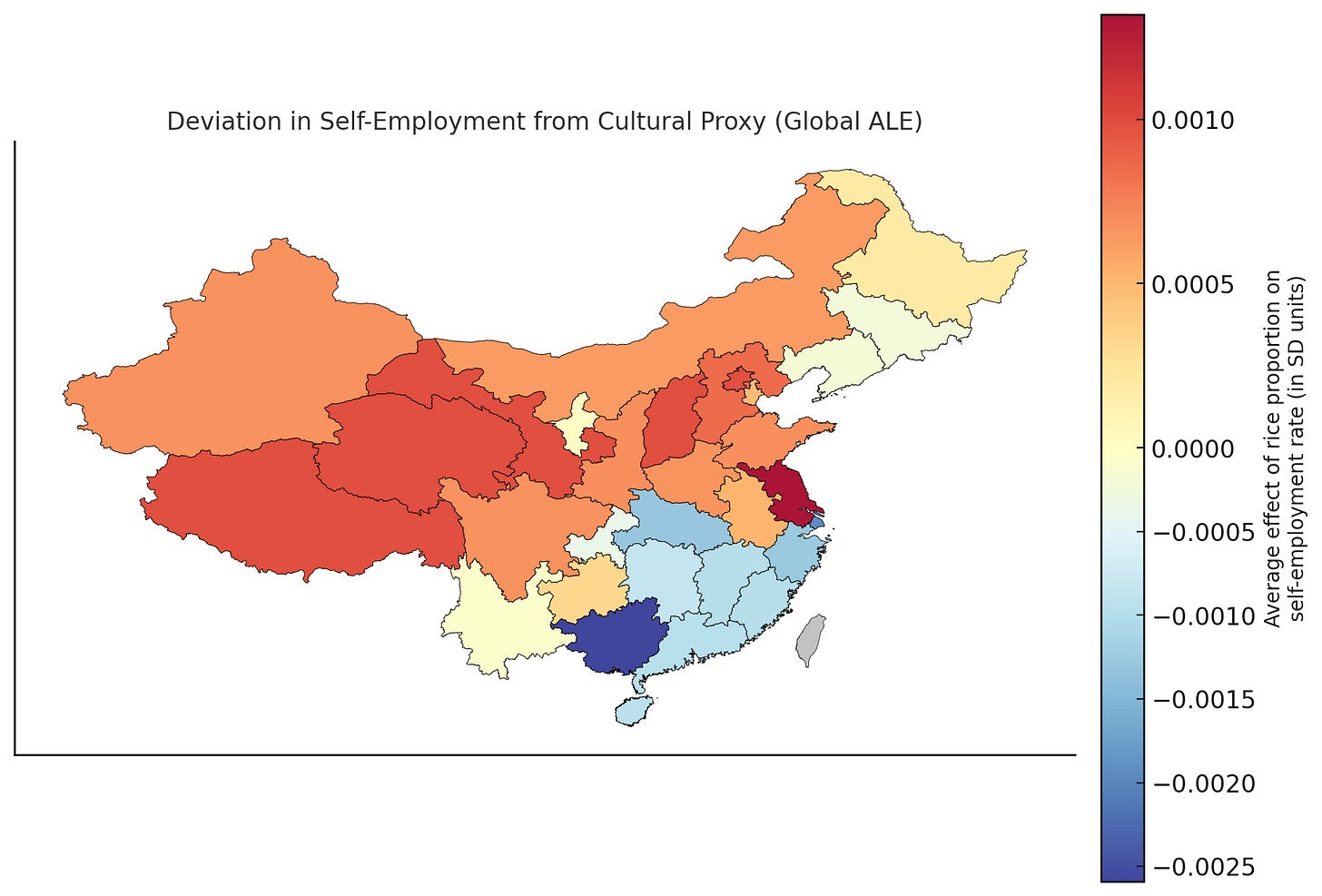

Rice intensity barely matters contemporaneously, but that doesn’t mean culture is irrelevant. We also compute a global ALE (Accumulated Local Effects) for the rice variable and average it within each province, then map those averages.

The map shows modest but geographically varied contributions: some provinces have a positive rice effect in the pooled nonlinear function, others a slight negative. That pattern is exactly what you’d expect from a slow-moving cultural trait: it modulates how provinces translate market and foreign-presence signals into self-employment, rather than acting like a year-to-year shock.

Thus we find that institutions and access (marketization, foreign firms) drive short-run moves. Culture (rice) shapes the baseline and the heterogeneity across space.

How to read these results

Self-employment is sticky. What happened over the last several years, and the province’s market and foreign-business environment, explains most of what happens next.

Culture shows up in the cross-section, not the week-to-week. Rice barely moves the short-run forecast needle, but the ALE map says it still matters for levels and nonlinear responses. Thus one must think of culture as a background operating system, not a push notification.

Now note that VIX is basically a non-event here. Once we control for domestic dynamics and year effects, global volatility adds almost nothing for provincial self-employment.

Policies aimed at market development and nurturing foreign business ecosystems are likely to co-move with self-employment dynamics, while cultural and historical endowments (proxied by rice) shape the baseline upon which those dynamics play out. This delivers a coherent narrative: institutions and market access drive the short-run, whereas culture conditions the long-run cross-sectional landscape.

Together, the estimates present a consistent picture: dynamic economic forces dominate short-run self-employment, while the rice proxy registers as a subtle, geographically patterned background factor, visible in the ALE-based map rather than in contemporaneous feature importance.

Policy Framework: Revitalizing the North through District Economies

Government as enabler, not investor

Executive summary

Northern China’s growth challenge is not a shortage of industrial parks or capital stock. Rather, Beihua faces a shortage of embedded productive ecosystems: dense supplier networks, vocational pipelines, proximate finance, and governance that rewards continuous upgrading. The recommended strategy is to develop industrial district economies at the city/county level, with government acting as institutional enabler rather than direct investor. This approach draws on Northern Italy’s experience of SME-driven clusters: many small, specialized firms linked by shared services, skills, and finance, competing globally through quality and reliability rather than scale alone. (European Commission, OECD, EconStor)

Expected outcomes within 24 months:

Higher supplier density and local input shares in targeted product families

Increased export orders and certifications (ISO/CE/UL) among SMEs

Measurable gains in value added per worker and apprentice placements

Reduced time-to-permit and improved credit access for qualifying firms

Guiding principles

Enable before you invest. Public support should condition on demonstrated linkages—suppliers, skills, finance, markets—not on floor space or ribbon cuttings.

Multiple small bets, disciplined by KPIs. Favor repeated, incremental upgrades across many firms over single “anchor” projects.

Institutional substitutes for missing informal trust. Where dense kin or guild networks are weak, build formal surrogates: cooperative finance, training compacts, supplier clubs, transparent dashboards. (Northern Italy’s cooperative banks, training linkages, and municipal coordination are the template.) (Credito Cooperativo - Federcasse, Iris, European Commission)

Governance that survives rotation. Codify tripartite district governance (government–firms–training bodies) with public roadmaps and metrics.

Program pillars (city/prefecture level)

1) District theses (≤3 per prefecture)

Define narrow product families where the locality has credible base stock (e.g., precision steel components; port/rail electrics; wind/EV sub-systems; cold-chain equipment). Publish a three-year District Thesis for each, binding all incentives to it.

KPIs: supplier count; local purchase share; export ratio; value added per worker. (EconStor)

2) Proximate finance for SMEs

Establish district credit windows at city commercial banks with risk-sharing guarantees tied to supplier upgrading and export orders.

Pilot cooperative/“popular” banking functions (relationship lending; receivables discounting along the chain).

Require ≥50% of new credit decisions to incorporate rolling performance data, not collateral alone. (Credito Cooperativo - Federcasse, Iris)

3) Vocational compacts

Create dual-track technician colleges co-governed by firms and city bureaus; pay for apprentices placed and multi-firm process upgrades delivered (lean/QC, digital MRP, safety, compliance).

Align curricula and certifications to each District Thesis; ensure skills are portable across cluster firms. (European Commission)

4) Supplier-upgrade sprints

Quarterly, co-finance tooling, certifications (ISO/CE/UL), metrology, and quality systems. Evaluate by orders landed, defect-rate reductions, and on-time delivery, not by patents or press releases. (International Labour Organization)

5) Export platforms

Stand up shared services for compliance, logistics, and market development (“export consortia”): pooled booths at trade fairs, reference designs, after-sales service, and documentation support for target markets. (Democracy at Work Institute, EconStor)

6) Governance and transparency

Constitute a tripartite district board (city economic bureau + 5–7 firms + training institution). Publish a 3-year roadmap and a quarterly public dashboard: supplier directory, wages/training, permit times, export wins, certification counts. (Bank of Italy, European Commission)

7) Procurement as first customer

Use municipal/SOE procurement to pilot district-relevant components and maintenance kits. Publish open standards and avoid vendor lock-in to diffuse capability gains.

8) Land and permitting discipline

Prioritize brownfield conversion and multi-tenant workshops. Enforce a “no tenant, no build” rule for new space; publish time-to-permit targets and meet them. (Oxford Academic)

Central government enablers (without crowding out)

Funding rules tied to embeddedness. Make transfers contingent on dashboard KPIs: local purchase share, supplier count, apprentice placements, export ratio, and permit times—rather than construction metrics. (OECD)

Regulatory sandboxes. Enable cooperative finance, supply-chain factoring, and performance-based guarantees that de-risk SME upgrades. (OECD)

Cadre rotation with guardrails. When seconding experienced southern officials to northern posts, require pre-agreed District Theses, signed MOUs with banks and training bodies, and time-boxed, publish-or-perish milestones to prevent assimilation into status-quo routines. (South China Morning Post)

Implementation roadmap

0–90 days

Select ≤3 District Theses per prefecture; publish roadmaps and dashboards.

Sign MOUs: (i) district credit window and guarantee pool; (ii) vocational compact with apprentice targets.

Identify brownfield assets for quick conversion.

3–12 months

Launch quarterly supplier-upgrade sprints and export consortia services.

First procurement pilots; first cohort of apprentices placed; initial certifications completed.

Dashboard live; time-to-permit targets enforced.

12–24 months

Scale financing windows; expand training capacity; second wave of certifications and export orders.

Independent audit of KPIs; adjust District Theses where targets are missed.

Monitoring & KPIs (reported quarterly)

Ecosystem: active suppliers (+ net new), local input share, supplier survival rate

Human capital: apprentices placed, certified technicians, wage progression

Markets & quality: export orders, certification counts, on-time delivery, defect rates

Finance & administration: approved SME loans, average rates/tenors, time-to-permit, brownfield utilization

Productivity: value added per worker, energy/material intensity per unit of output

Risk management

White-elephant risk: Enforce “no tenant, no build” and link all funding to District Theses and KPIs. (Oxford Academic)

Capture/club dynamics: Rotate firm representatives on the district board; publish minutes and performance data.

Measurement gaming: Use third-party audits and outcome-based triggers (e.g., export invoices, certification IDs).

Bureaucratic drift: Time-bound milestones; automatic funding taper when KPIs are missed.

What not to do

No megaprojects untethered to a District Thesis. Hardware without ecosystem becomes a “cathedral in the desert.” (Encyclopedia Britannica, Oxford Academic)

No single-anchor dependency. District resilience comes from diversified networks of specialized SMEs, not one champion investor. (European Commission, EconStor)

No generic subsidy zones. All support must be tied to supplier upgrading, skills formation, and export capability within the thesis.

Why this fits China’s moment

It matches the constraint: macro headwinds make capital expensive and confidence scarce; district wins (supplier upgrades, export orders, apprentices placed) rebuild both, fast. (South China Morning Post)

It leverages the cadre push: southern governance know-how is catalytic if it’s bound to transparent theses, dashboards, and time-boxed deliverables. (South China Morning Post)

It copies what’s portable from Northern Italy: SME networks, cooperative finance, vocational depth, and associational governance—local institutions supplying what capital alone cannot. (European Commission, Credito Cooperativo - Federcasse, Iris)

One-page execution checklist (city level)

☐ Publish ≤3 District Theses and KPIs

☐ Sign bank MOU (credit window + guarantee pool)

☐ Sign training compact (apprentice targets; curricula)

☐ Launch upgrade sprints (quarterly)

☐ Stand up export platform (shared compliance/logistics)

☐ Constitute tripartite board; publish dashboard

☐ Implement “no tenant, no build” and permit SLAs

This framework positions government to manufacture embeddedness—the core asset that compounds over time—so northern cities can convert existing industrial capabilities into resilient, high-productivity district economies. (OECD)